Irish Immigrants in America

|

Even before the Irish emigration to America as the result of the Great Famine, life in Ireland was cruel. The Irish lived for centuries under English oppression, poverty and disease; they knew that it was not about to change soon. Early immigrant letters described America as a land of abundance and urged those left behind to join them. Going to America became the dream of those Irish who just wanted a better life; however, they did not know what they would encounter.

As the ship was docking, these immigrants learned that life in America was going to be a battle for survival. The Irish immigrants were the poorest of the poor and had no means of moving on, so they were packed into poorhouses at the port of arrival. They could not obtain employment as they were considered the lowest form of human beings, replacing the black slaves. To the landowners and employers, the blacks were considered property and some, who had invested in these slaves for generations, felt that the slaves were more valuable than the Irishmen. The Irish begged on every street corner as all the posted help wanted ads stated 'NO IRISH NEED APPLY'. These signs became known as NINA's.

When the Great Famine hit Ireland, the people did not have any choice but to emigrate. All of the workhouses were filled to the brim and they worked in exchange for sustenance. The landlords discovered that they could buy the poor passage to America cheaper than to care for them in Ireland. Recent letters from America told of the discrimination of the Irish and that the life they lived was of shame and poverty.

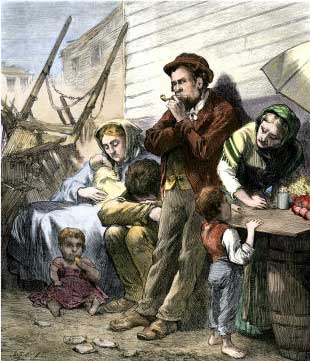

At the influx of the famine immigrants, the Irish were forced to live in cellars and shanties. Most major cities had their own 'Irish Town' or 'Shanty Town' where they clung together with their own kind. They were not welcome in neighborhoods because they were not familiar with plumbing and running water, which bred conditions of sickness and early death. Their Irish accent and backward dress resulted in ridicule and their poverty and illiteracy resulted in scorn. In early drawings they were portrayed as ape-like leprechauns with shoes too big, hats too small, and clothes that had been out of style for decades. Their Catholic beliefs were also ridiculed by the large majority of English-American Protestants who, not-so-long before, were immigrants themselves.

Instead of apologizing for themselves, they united and took offense, usually resulting in violence. Solidarity was their strength and they helped each other survive; but it was their faith and dogged determination to become Americans that led to their survival.

The famine-Irish arrived at a time of need for America, as the country was growing and it needed men to do the heavy work of building bridges, canals, and railroads. It was hard, dangerous work, and it was mostly Irishmen that filled the most laborious and dangerous jobs. Not only the men worked, but the women did as well. They became chamber maids, cooks, and the caretakers of children. The Protestants thought that this type of work was only fit for servants. The Negroes were servants and, if not Negroes, then Irishmen would take their place. The blacks hated the Irish and it appeared to be a mutual feeling.

The Irish were unique amongst immigrants. They loved America but never gave up their allegiance to Ireland, nor did they give up their hatred of the English. The Irish used brutal methods to fight brutal oppression. They loved America and gladly fought in her wars. During the Civil War they were fierce warriors forming, among other groups, the famous Irish Brigade. A priest accompanied them and they would pray together before charging into the enemy, even against terrible odds. Their faith guided them and they felt the English might have a better life on earth but they were going to have a better life after death.

The days of "No Irish Need Apply" passed, and the St. Patrick's Day parade replaced violent confrontations. The Irish not only won acceptance for their day but persuaded everyone else to become Irish at least for St. Patrick's Day.

At the turn of the century, the appearance of large numbers of Jews, Slavs, and Italian immigrants led many Americans to consider the Irish as an asset, and their Americanization was now recognized. Hostility shifted from the Irish to the new nationalities. Through poverty and sub-human living conditions, the Irish tenaciously clung to each other and, with their ingenuity for organization, they were able to gain power and acceptance.

In 1850, at the crest of the Potato Famine immigration, Orestes Brownson, a celebrated convert to Catholicism, stated: "Out of these narrow lanes, dirty streets, damp cellars, and suffocating garrets, will come forth some of the noblest sons of our country, whom she will delight to own and honor."

In a little more than a century later his prophecy came true. Irish-Americans had moved from the position of the most despised citizens to the highest in the land, when John F. Kennedy became the first Irish-American Catholic President.

|

Portrait

of President John F. Kennedy, Photographic Print Buy at AllPosters.com |

Disclaimer: LittleShamrocks.com is an affiliate website that receives commissions from sales of the products listed. We have purchased and sampled many, but not all, of the products on these pages.

© Copyright LittleShamrocks.com. All Rights Reserved.